How to store a float number in the memory?

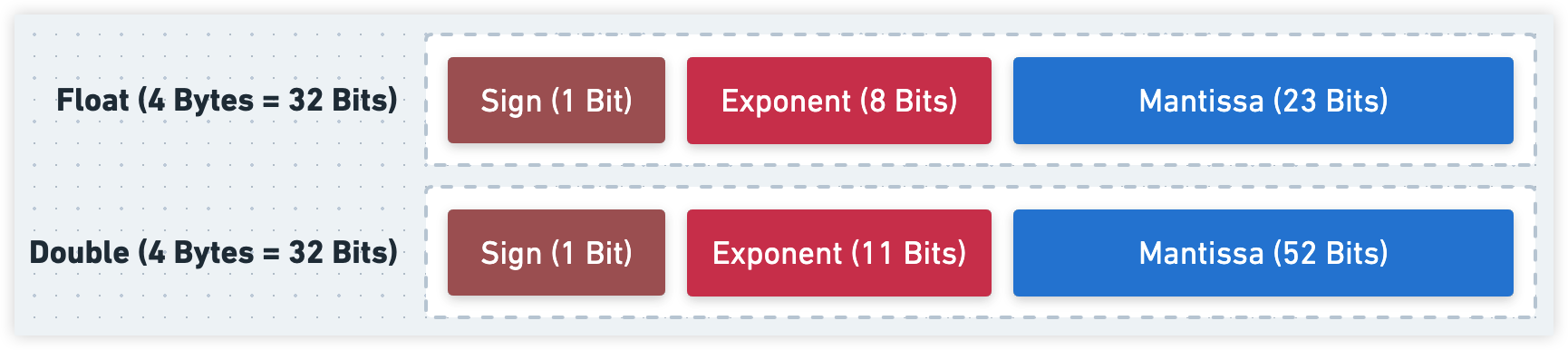

In C language, the decimal numbers have two lengths, float and double. Their lengths are constraint compared with integers. The float occupies 4 bytes, and the double needs 8 bytes.

We know the decimal numbers have two parts, the integer part and the decimal part. How do we store a decimal number? The easiest way we can figure out is to store the two parts separately. A decimal number saved by the way above is the fixed point number. Of course, we also have the floating point number.

We always say the decimal number as the floating-point number, but actually, they are not equal. The decimal numbers and the integers are the same groups, the floating-point number is not a number type but a number storing format corresponding to the fixed-point number. You can save an integer using the floating-point number format.

What are the floating-point number and fixed-point numbers?

Fixed-point number

The “Fixed point” means the decimal point is fixed. It can’t move forward or back. If we use 4 bytes to save an unsigned fixed-point number and specify the first 16 bits and the end 16 bits to store the integer part and the decimal part separately, the max value is 2^16 - 2^-16 very close to 2^16 when all the bits are 1, the min value is 0.

The last decimal bit might be a precise figure or an approximate figure, but all other bits are exact, so the fixed-point number has 31-32 precise bits.

Using a fixed-point number can get higher precision, but its value range is too small and cannot store a large number.

If we want to store a large number 1.2*10^30, using the fixed point number format will need dozens of bits. The large number will cost a large memory space. Like the number above, I didn’t write it as 12000000...00000 but used an exponential format (scientific notation). This format is shorter and clearer.

Floating point number

We should first understand the scientific notation before understanding the floating-point number.

flt = (-1)sign × mantissa × baseexponent

- The

fltmeans float point number - The

signused to say the number is positive or negative - The

baseis the base number, and its value is greater, or than 2, 2 means it’s binary, 10 means it’s decimal, and 16 means it’s hexadecimal. Usually, we use the decimal number in mathematics. eg: 2000 = 2.0 * 103 - The

mantissahas to be in the range from 1 to base, which means there is only one digit before the decimal point. - The

exponentis a decimal integer, can be negative or positive.

Let’s take an example of how to transform a decimal number 19.625 to floating-point format.

When the base is 10, we can easily get the result 1.9625 * 101.

If we set the base to 2, there is not easy to get the result directly. We need some calculations.

- First, we transform the integer part to binary format.

19 = 1×24+0×23+0×22+1×21+1×20 = 10011 - Then, we transform the decimal part to binary format.

0.625 = 1×2-1+0×2-2+1×2-3 = .101 - Combine the integer part and the decimal part

19.625 = 10011.101 - Finally, convert the binary decimal number to floating point format

10011.101 = 1.0011101×2^4

In the example above, we see that the exponent is the decimal point’s offset.

- The exponent is negative. We can left shift the decimal point to get the original value.

- The exponent is positive. We can right shift the decimal point to get the original value.

In other words, the position of the decimal point was changed after converting to floating-point format. The offset depends on the exponent, so we call this decimal number displaying format floating-point.

Storing a binary floating-point number

First, we should know what parts of a point number we should save. In the expression above, we can find four variables.

flt = (-1)sign × mantissa × baseexponent

- sign

- mantissa

- base

- exponent

The sign can only be 0 or 1, so it needs 1 bit to save.

The base must be 2 in binary floating-point numbers, so we don’t need to save it.

The mantissa and the exponent occupy different spaces in the float and the double. I made a char below to display the memory layout.

When storing the mantissa part, we haven’t to record all parts of the floating-point number because its integer part must be 1, so we need to store its decimal part.

The exponent is an integer, so its value might be negative. In normal, we can save it as saving a fixed point integer, the highest bit is a sign bit, but the floating-point number doesn’t use this. When saving an exponent, we firstly add a median to it. In float, the exponent occupies 8 bits of memory, its max value is 255, and the median is 127. And when calculating the number, we set the value minus 127 to get the correct exponent.

It’s better to do than to talk. Let me demonstrate it.

We use the example 19.625 again, we know 19.625 = 1.0011101*2^4, contrast it with the floating point format expression, we can get these values:

sign=1mantissa=1.0011101exponent=4

We only save the decimal part of the mantissa, then filling the vacant bits with 0, its binary is 001 1101 0000 0000 0000 0000(23 Bits). The exponent is 4, 4 + 127 = 131, the binary of 131 is 1000 0011. Finally putting them together:

0 - 1000 0011 - 001 1101 0000 0000 0000 0000

The storing accuracy

For decimal fractions, we use the Euclidean algorithm[1] to convert its integer part to binary format. A length-limited integer surely can be converted to a length-limited binary number. But the decimal part has some differences. When converting the decimal part to binary, we continuously divided it by two[2] until the remainder equals zero, but not every decimal can be multiplied to the end. Only the tail is 5 can do this, so a length-limited decimal might not be converted to a length-limited binary.

The mantissa of the float and the double is length-limited. When the decimal part of a floating-point number is too long, the over part would be ignored. In other words, the floating-point number might not store an exact number but an approximate value

IEEE 754 standard

The IEEE 754 standard is the most popular floating-point number standard, and you can get the detailed info on Wiki, it’s a genius-like idea. In IEEE 754, the scientist designed two specific values.

Specific values

When all exponent bits are 1, we don’t think it’s a normal floating-point number but a specific value.

- If all bits of the mantissa is zero, it means infinity.

- The sign is 1 means negative infinity.

- The sing is 0 means positive infinity.

- If having any bit of the mantissa is not zero, we think this value is invalid or has not been initialized yet.

Denormal number

When all bits of the exponent are zero, we will make this value a subnormal number.

For normal floating-point numbers, the hidden integer part of the mantissa is 1, and the exponent value in the memory needs to subtract the median(In float, is 127) to get the correct value.

But in denormal numbers, the rule changed. The hidden integer part of the mantissa becomes 0, not 1, and we need to use 1 minus the median to get the exponent. For float, the exponent is 1 - 127 = -126. For double, the exponent is 1 - 1023 = -1022.

For denormal numbers, its value equals zero when all bits of the mantissa are zero. If the sign bit is 1, its value is negative zero (-0), otherwise it is positive zero (+0).

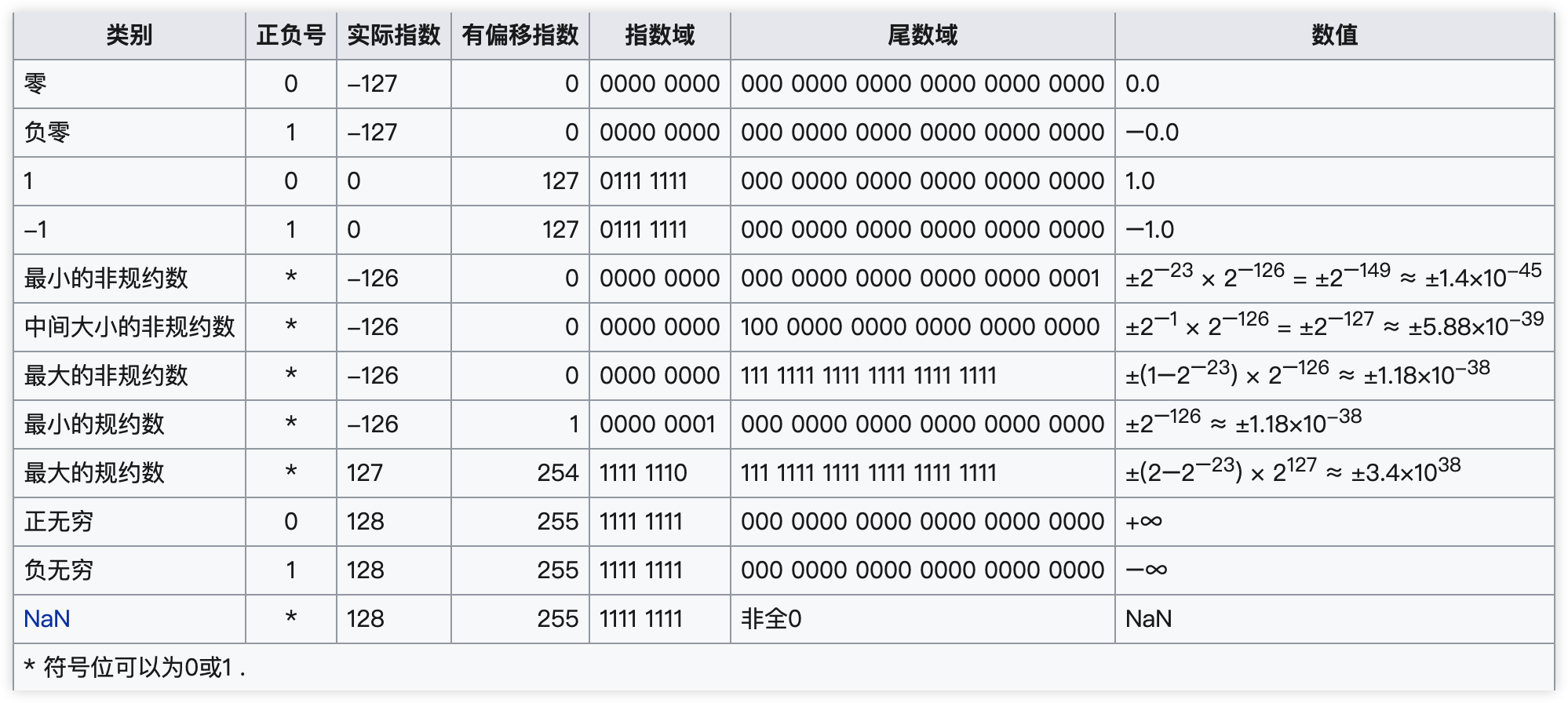

I found a list from Wiki that displayed all boundary values of the single-precision floating-point number (Float).

The reason why import the denormal numbers is the minimum value of the normal values is still too large for scientific calculations. Take Float as an example. The minimum value of its normal values is 2-126. When all mantissa bits are zero, the minimum value of the denormal values is 2-149, which is much smaller.

If you look carefully, you can find the following number of the minimum value of the normal values is the maximum value of the denormal values. They are closely linked. Let me show you the memory layout.

- Max denormal value

0 - 0000 0000 - 111 1111 1111 1111 1111 1111= 1.11…111 * 2-167 - Min normal value

0 - 0000 0001 - 000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000= 1.0 * 2-126

The Min normal value minutes 1 is the Max denormal value. Wonderful!

Rounding rules

The standard defines five rounding rules. The first two rules round to the nearest value; the others are called directed roundings:

Roundings to nearest

- Round to nearest, ties to even – rounds to the nearest value; if the number falls midway, it is rounded to the nearest value with an even least significant digit; this is the default for binary floating-point and the recommended default for decimal.

- Round to nearest, ties away from zero – rounds to the nearest value; if the number falls midway, it is rounded to the nearest value above (for positive numbers) or below (for negative numbers); this is intended as an option for decimal floating-point.

Directed roundings

- Round toward 0 – directed rounding towards zero (also known as truncation).

- Round toward +∞ – directed rounding towards positive infinity (also known as rounding up or ceiling).

- Round toward −∞ – directed rounding towards negative infinity (also known as rounding down or floor).

Example of rounding to integers using the IEEE 754 rules

| Mode | +11.5 | +12.5 | −11.5 | −12.5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| to nearest, ties to even | +12.0 | +12.0 | −12.0 | −12.0 |

| to nearest, ties away from zero | +12.0 | +13.0 | −12.0 | −13.0 |

| toward 0 | +11.0 | +12.0 | −11.0 | −12.0 |

| toward +∞ | +12.0 | +13.0 | −11.0 | −12.0 |

| toward −∞ | +11.0 | +12.0 | −12.0 | −13.0 |

Compared with the fixed-point number, the floating-point number sacrifices accuracy for a more extensive range of values.

Euclidean algorithm, continuously divide by 2 until the remainder equals zero. ↩︎

Continuously multiply by two until the remainder equals zero

- Divide the number by 2.

- Get the integer quotient for the next iteration.

- Get the remainder for the binary digit.

- Repeat the steps until the quotient is equal to 0.